Global temperature variation, both warming and cooling, has occurred naturally throughout Earth’s history. We know this as we have employed a number of techniques, such as analysis of ice cores, to collect in-depth data on temperature variation and atmospheric gas compositions over extended timescales.

Such analyses have told us that carbon dioxide (CO2) levels are strongly correlated with global temperature and that CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere have increased to record levels in record speeds over the last 100 years. This is purely a result of human activity. We know that as CO2 and other greenhouse gases continue to rise at an unprecedented rate, so do global average temperatures.

With such rapid temperature change, life on Earth can simply not adapt fast enough to survive. Entire species and even ecosystems are under threat from this phenomenon, none more so than coral reefs.

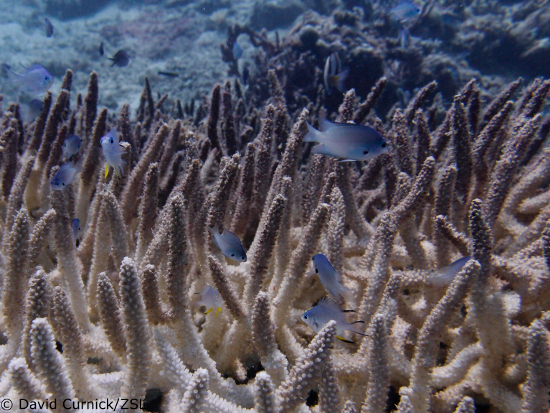

Bizarrely, the imminent threat of temperature change is not to the reef building corals directly, but to the algal symbionts that are retained within their tissue. The survival of most species of reef building coral is dependent on these algal symbionts (‘zooxanthellae’) which are engulfed by and live inside their coral host. Within the polyp, these zooxanthellae photosynthesise, a process that converts sunlight into a form of energy that both the algae and their coral host can utilise for growth. Typically, around 70% of a coral’s energy will come from this relationship. Under temperature stress, coral polyps are known to expel these symbionts in a process known as bleaching (without colourful algae within the corals, they turn translucent and appear white). If temperatures remain high, coral polyps cannot obtain new zooxanthellae and they begin to starve. Experimental research has shown this expulsion occurs as a result of algal death at around 30 degrees. Interestingly, the corals themselves were found to withstand temperatures up to 36 degrees before they began to die off.

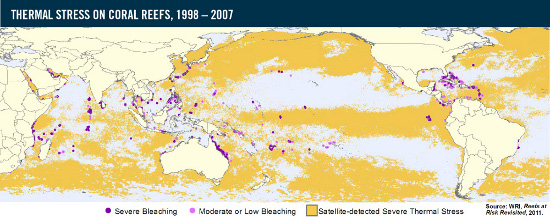

Temperature-induced bleaching events are known to cause mass mortality of corals. In 1998 alone, a single mass bleaching event killed an estimated 16% of the world’s coral reefs. EDGE species such as elkhorn coral are particularly susceptible to bleaching due to their preferred habitat of shallow reefs (0.5-5m depth). At these depths temperatures are typically higher and sunlight, another catalyst of the process, is more intense. With global warming set to continue, we can expect more frequent, more intense and more widespread global bleaching events.

Promisingly however, observations of previously bleached reefs have revealed impressive abilities to recover as long as subsequent threats are neutralised. As such, it is vital that localised, threatening and unsustainable activities are rapidly eliminated from fragile coral habitats. This is something that EDGE is working hard to achieve.

Two EDGE Fellows, Ditto dela Rosa and Grace Quiton are currently working to conserve reef-building coral species. Their projects focus on enhancing our knowledge of EDGE corals and furthermore designing and implementing low cost, community based conservation projects which will work to protect these delicate marine habitats.

In the long term however, large scale international efforts are needed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and stem global warming. This is the only way to reduce the prevalence of catastrophic bleaching events.