In our study, published in Science Advances, we found that the most important areas of the planet for evolutionarily unique and isolated species are poorly protected and face higher levels of both current human activities and future climate change.

In the study, led by collaborators at Ben-Gurion University, we identified regions of the planet with large concentrations of unique evolutionary history restricted to very small areas of the planet. These are places where many long branches of the tree of life overlap and are isolated to very small areas. Within these areas are many unique species that represent large accumulations of evolutionary history and are found pretty much nowhere else on Earth.

When we mapped this for more than 30,000 species of the world’s tetrapods—that is, amphibians, birds mammals and reptiles—we found that the regions containing disproportionately large accumulations of range-restricted (or ‘endemic’) and unique species mostly occur in mountainous tropical regions, in the southern hemisphere, along mountain ranges, and on islands. Particularly important regions for tetrapods include Caribbean islands, Central America, Madagascar, Sri Lanka, the southern Western Ghats in India, and New Guinea.

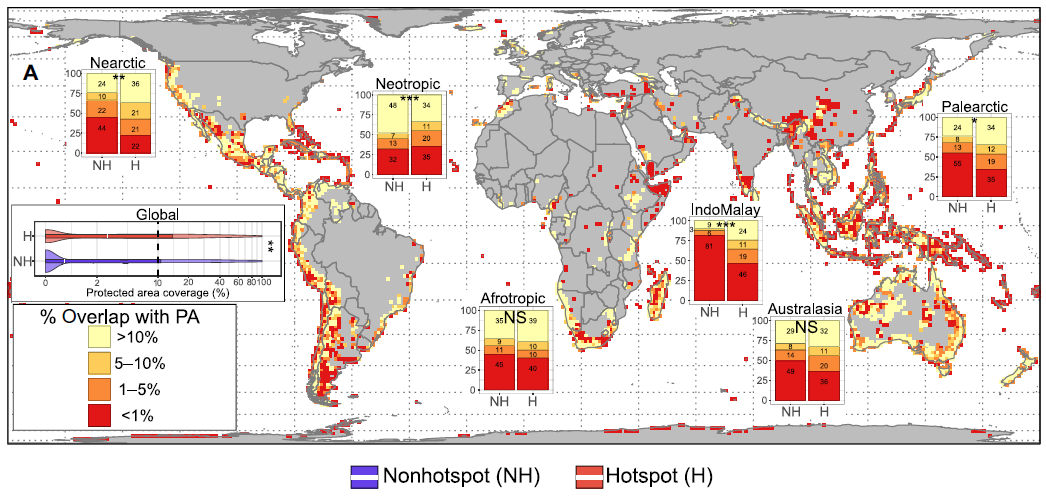

Some of these regions have previously been prioritised for conservation action, but many are currently receiving little formal protection. Unfortunately, around 70% of the most evolutionarily unique and endemic regions on Earth have less than 10% of their area covered by protected areas. Some of the most irreplaceable regions lacking protection include the Caribbean islands, the Horn of Africa, the highland forests of Cameroon, and the Solomon Islands.

We also quantified the extent to which human activities and climate change threaten these key regions. Worryingly, infrastructure, the conversion of natural land for agriculture, and high human population density are more prevalent in areas of greatest irreplaceability than outside them. The footprint of human activity is, on average, 75% higher in these most irreplaceable regions.

In addition to the immediate impacts of human activities, we found that the rate of current climate change is 160x higher in the most irreplaceable regions. Alarmingly, these areas are set to experience rates of future climate change around 20% higher than other areas. Given that many of these regions are concentrated along coastlines or on islands that are currently under intense human pressure, there is limited potential for unique species to shift to more suitable climates as the environment rapidly changes.

One such species already feeling the combined effects of human pressure and a rapidly changing climate is the Western Swamp Turtle (Pseudemydura umbrina). The turtle, which can sometimes be found masquerading as an algae-covered teddy bear, is on the brink of extinction, with fewer than 300 individuals thought to be left in the wild. Due to the aridification of its natural swamp habitat, it is the first vertebrate species for which climate change has driven assisted colonisation efforts and is on the brink of extinction.

However, it is not too late to change the course we are on to avoid even greater impacts to the world’s weird and wonderful species. Many of the species found within these most irreplaceable regions are EDGE species – the most evolutionarily unique and threatened animals on Earth. ZSL’s EDGE of Existence programme is a global initiative dedicated to the safeguarding of threatened evolutionarily history, and supports on the ground conservation efforts to conserve EDGE species around the globe.

As the next United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) looms, our study emphasises the importance of implementing robust policies to curtail greenhouse gas emissions. This is vital to safeguard the most irreplaceable regions of the planet, and in turn aid the survival of thousands of unique species that represent millions of years of irreplaceable evolutionary history.